Holocaust Remembrance Day: Forgetting the Holocaust Would Mean Killing a Second Time

Raffaella Di Marzio

“Forgetting the Holocaust would mean killing a second time” are the words of Elie Wiesel, a Holocaust survivor and defender of human rights.

Holocaust Remembrance Day is an international observance, commemorated on 27 January each year as a day dedicated to remembering the victims of the Holocaust. It was designated as such by Resolution 60/7 of the United Nations General Assembly on 1 November 2005, during its 42nd plenary meeting.

The Nazi genocide caused the death of approximately six million Jews, as well as thousands of Roma and Sinti, people with disabilities, Soviet prisoners of war, and homosexuals. Others, such as Jehovah’s Witnesses, socialists, and communists, were targeted because of their religious beliefs and political ideas.

There are countless stories of survivors of the concentration camps, and it is especially important on this day to focus on them, because only the memory of those who lived through that tragedy has the power to awaken in us resistance to every form of oppression and the courage to oppose violence in defence of every human being.

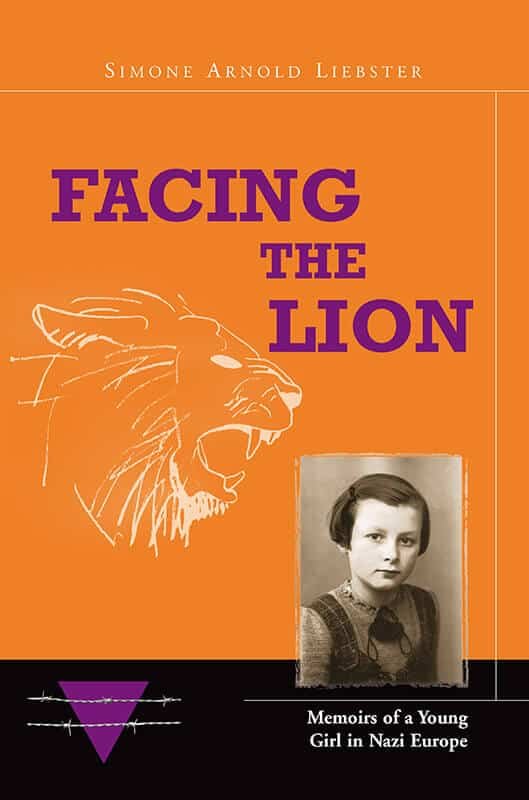

One such story is that of Simone Arnold‑Liebster, born in Alsace on 17 August 1930, who, together with her parents, belonged to a group of Jehovah’s Witnesses in Mulhouse.

Jehovah’s Witnesses were systematically persecuted in the German Reich and in large parts of Nazi-ruled Europe. More than half of the believers—at least 10,700 German Jehovah’s Witnesses and 2,700 from the occupied countries of Europe, women just as much as men—suffered direct persecution, mostly in the form of imprisonment. About 2,800 Jehovah’s Witnesses from Germany and 1,400 others from Nazi‑occupied Europe were imprisoned in concentration camps. They were stigmatised with a special identification mark, the “purple triangle”, and they constituted one of the largest groups of prisoners in the early concentration camps. 1,250 of those persecuted were minors, and 600 children were taken away from their parents by the Nazi state. At least 1,700 Jehovah’s Witnesses lost their lives as a result of National Socialist tyranny. Among them were 282 Jehovah’s Witnesses executed for conscientious objection. A further 55 conscientious objectors died in custody or in penal units. This is the largest group of conscientious objectors under National Socialism. (Data drawn from: https: https://alst.org/it/la-storia/)

Foundation website: https://alst.org/en/the-foundation/

Simone’s story, together with many others, is told on the website of the Arnold Liebster Foundation, whose founders address visitors with the following words: “May these reflections, testimonies, and narratives help our visitors understand that intolerance leads to exclusion, persecution, and ultimately annihilation. May these historical accounts likewise inspire strength and courage in those suffering oppression of all kinds.”

Simone and Max Liebster

For Simone, school became a place where she had to put her religious principles to the test every day, starting with the German invasion in 1940, as the “Germanisation” of Alsace turned teachers into fanatical National Socialists. Simone Arnold‑Liebster suffered psychological and physical abuse, was expelled from secondary school, and was eventually torn away from her mother in April 1943 and taken to a Nazi reformatory in Constance. There she was forced to perform hard labor and to endure psychological abuse. Had liberation not arrived, she would have been transferred to a concentration camp at the age of fifteen.

Alsace, 1930s. Simone, a happy and carefree young girl, gradually comes to know poverty, injustice, and intolerance, and eventually the anguish of war, arrests, and interrogations. At school, in the city, and everywhere else, she finds herself increasingly alone in the face of the “Lion”, the Nazi system voracious for its prey.

Constance, 8 July 1943. The heavy door of the Wessenberg Institution is slammed shut. Simone is cruelly separated from her mother and interned in a Nazi reformatory. Deprived of all her joys. Alone in the Lion’s den…

With a lively style and even a touch of humor, Simone Arnold Liebster recounts her survival in a world that had suddenly become tragic and harsh, and the victory of an ordinary, vulnerable young girl fighting against the Lion. Her autobiography gives an identity and a face to the forgotten victims of National Socialism. It is also a compelling testament to the power of conscience to resist all forms of manipulation, even under extreme pressure.

(https://editions-schortgen.lu/en/book/facing-the-lion-simone-arnold-liebster/).